Christian symbols

Where did they come from?

Were the symbols divinely inspired, or just Jewish or Pagan upgrades? Were liturgical rites and rituals, and the design of church buildings copied from tried-and-tested pre-Christian sources? And the Bible, with its abundance of apparently mythical events, was the Bible plagiarized from pagan Greco-Roman texts?

While John H Newman's essay addresses those questions in his 1845 Essay on the Development of the Christian Doctrine, here we look at the origin of some of the most common Christian symbols:

|

Cross

The cross is the most universal symbol for Christians (probably since the fourth century) to represent the sacrifice of Jesus for humanity’s salvation.

That raises a question: why did the cross, a pagan execution tool, become the symbol of salvation?

Jewish chief priests accused Jesus of blasphemy (claiming to be the Son of God), and blasphemy was a capital offence under Jewish law. However, under Roman law, the Jews had no authority to carry out executions and therefore they appealed to the governor (Pontius Pilate) to administer the punishment.

Ironically, blasphemy wasn't a capital offence under Roman law, so the charge got a quick legal makeover, weaponised as 'treason' due to Jesus' “claim to be a king” (Luke 23:2).

This satisfied the Jewish leaders' bloodlust, not only because Jesus would be executed, but it would be through crucifixion - a nasty and brutal method which the Romans had adopted from the pagan empires of Persia and Greece.

So crucifixion was not a rabbinic method, rather it was pagan. It was not employed by the Jews because crucifixion was a slow, torturous ordeal - an intentionally degrading public spectacle designed to extend suffering. Jewish law preferred quicker, more discreet forms of execution: stoning, burning, beheading or strangulation.

While the cross appears in many forms in pre-Christian art, symbolizing life, balance or protection, it was not associated with crucifixion. In Christianity, however, the cross is always a reference to the crucifixion of Jesus and the salvation it represents.

Despite this ancient background of the cross, it didn't immediately become a symbol of Christianity, since they didn’t want to associate their faith with a method of torture and disgrace. Over time, however, the cross came to symbolize not just suffering and death, but redemption and eternal life.

Yet another example of God's prefiguration at work.

(more...)

Crucifix

"Crucifix" is from the Latin cruci fixus, meaning "one fixed to a cross". It's a cross that includes a representation of a corpus - usually the body of Jesus, emphasising his suffering and sacrifice.

A cross without the corpus emphasises that Christ has risen. The crucifix shows the price; the cross shows the prize. The crucifix shows His pain, His price, His passion; the cross shows His power, His peace, His promise.

This death/life contrast might explain whey the cross (without a corpus) is more commonly seen than a crucifix. But we must remember that Christ’s suffering and death are not just a past events — they are a present, saving reality.

The sacrifice is central to salvation. The crucifix keeps that truth visually in front of believers, emphasising the cost of sin and the depth of God’s love.

(more...)

Fish (Ichthys)

The Greek word for "fish" is ΙΧΘΥΣ (Ichthys), which also serves as an acronym for Ιησοῦς Χριστός Θεοῦ Υἱός Σωτήρ (Jesus Christ God's Son Saviour).

It is believed that early Christians used this symbol to secretly communicate with each other due to widespread persecution and the need for discreet identification. Christianity was seen as a threat to the pagan religion of the Romans. Openly declaring one's Christian faith could lead to arrest, torture, or even execution. In such a society, early Christians needed a simple, inconspicuous symbol, such as the fish, to help them recognise one another without drawing unwanted attention.

Since the fish was already a common symbol in Greco-Roman culture (representing fertility, life and abundance), scratching its outline wouldn’t arouse suspicion.

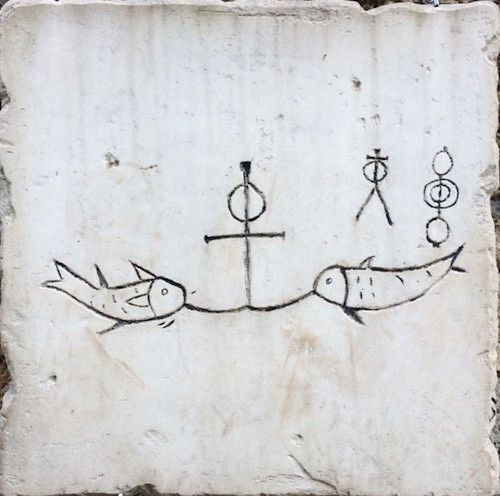

Other secret symbols were also used for the same purpose, including the Anchor, the Chi-Rho, the Alpha and Omega and the Dove.

Here's an example of the anchor and fish which can be seen in the Catacombs of Domitilla.

(more...)

Dove

The dove was a symbol for both Early Christians and pre-Christian Pagans, but it had quite different symbolic identities.

Doves symbolised:

- Divine messengers

- Paganism: A courier between gods and humans

- Christianity: Representing the Holy Spirit, carrying God’s message to humans

- Love

- Paganism: Romantic and sexual passion and fertility; sacred to goddesses such as Inanna/Ishtar, Astarte, Aphrodite/Venus

- Christianity: God’s selfless and unconditional spiritual love (agápē)

- Peace and reconciliation

- Paganism: Peace and reconciliation between lovers or tribes

- Christianity: Peace with God and reconciliation through Christ

- Sacrificial offering

- Paganism: Offered to fertility goddesses

- Christianity: Christ’s ultimate sacrifice

- Soul or spirit of the deceased

- Paganism: Seen as a departing human soul ascending to the divine realm

- Christianity: Representing the Holy Spirit, giving life and guiding the soul to eternal life with God

(more...)

- Divine messengers

Alpha and Omega

The characters A and Ω are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and symbolise that God is the beginning and the end (Rev. 22:13). Since God is eternal and has no beginning or end, the spiritual meaning of the phrase is that He is the 'Beginner' and also the 'Ender' (the Last); there was no 'before' God, and there will be no 'after' God.

We're unaware of any Pagan use of the same two Greek letters.

(more...)

Lamb (Agnus Dei)

Lambs are born in spring, so it is not surprising that, for pagans, they symbolised fertility and renewal. Their innocence and gentleness made them suitable offerings to deities of agriculture, such as Demeter and Ceres, and to goddesses of love, such as Aphrodite. These offerings were intended to ensure favourable harvests and fertility.

In contrast, ancient Israelites sacrificed lambs to the one God (Yahweh) as a ritual sign of repentance for sin, so that they might be restored to their covenant relationship with Him.

And, in contrast to the ancient Israelites, Christians refer to John the Baptist calling Jesus 'the Lamb of God' (John 1:29). Jesus was the ultimate sacrificial offering, taking away the sins of humanity through His death. That completely replaced the old sacrificial rites.

Agnus Dei is Latin from the Greek Ἀμνὸς τοῦ Θεοῦ, meaning 'Lamb of God'. Notice that the slaughtered lamb in the symbol is not a limp carcass; rather, it has a sprightly pose, representing the risen Christ triumphant over death. It’s a vivid way to declare not only sacrifice, but also victory.

(And in case you’re wondering why the lamb in the symbol nearly always faces the same way, it’s because since medieval times it's been a heraldic tradition for the lamb to face the dexter, often holding a flag over its shoulder with its right foreleg.)

(more...)

Chi-Rho

The Greek letters Χ (chi) and Ρ (rho) are the first two letters of Χριστός (Christos). This monogram of Christ is one of the earliest Christian symbols and is still used today.

We're unaware of any Pagan use of the same monogram, though it did have non-Christian, non-religious uses in the ancient Greco-Roman world. Scribes of Greek manuscripts sometimes added χρ in the page margin, as a shorthand for χρηστόν (good, useful).

Pre-Constantinian coins also show a chi–rho mint mark on the reverse. (Click image to enlarge.)

(more...)

Crown of Thorns

The Crown of Thorns symbolises the suffering and mockery Jesus endured during his Passion. It is impossible for us to imagine the intensity of the physical pain of having nails driven through the hands (or wrists) and feet when he was hung on the cross, which must have been far worse than the pain inflicted by the crown, or even the scourging.

The primary purpose of the Crown of Thorns, as with the purple robe, was to mock Jesus.

Crowns, wreaths and other head adornments were common in pagan cultures as symbols of victory or honour, and were made from laurel, myrtle or other leaves. A crown of thorns, therefore, was the antithesis of the pagan use of crowns, a mockery of kingship.

Although the Crown of Thorns was intended to ridicule, it actually became a profound paradox; it served to reveal his true identity as the King of Kings.

(more...)

Anchor

In Christianity, the anchor is a powerful symbol of hope, stability and faith:

“hope as an anchor for the soul” (Heb. 6:19).

As with the Fish and Chi-Rho symbols, Early Christians in the first-third centuries would draw an anchor as a discreet symbol of hope and faith, to avoid persecution.

Most likely, ancient Greek and Roman mariners used the symbol as a protective charm. The anchor symbol also appears in Greco-Roman philosophy.

However, even though those societies were pagan, we're unaware of any religious use of the anchor symbol.

(more...)

Heart

The heart symbol screams 'love'; whether it’s divine, romantic, a social media 'like', or just our way of saying "I really, really like this thing a lot".

In religion, the symbol represents Jesus’ divine love and compassion for humanity. It is depicted frequently in Catholicism, less so in Protestantism, and practically never in Judaism or Islam.

But it didn't begin as a Christian symbol; rather, it was the ancient Greek and Roman pagans who (as explained here) sowed the seed around the seventh century BCE.

From the twelfth century, the heart became a symbol of Christ’s divine love and sacrifice. The Sacred Heart of Jesus, often depicted as a flaming heart, began appearing in devotional texts by mystics such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Gertrude the Great.

From the thirteenth century, romantic symbolism emerged and, over time, became more consistent in shape, without any of the enhancements shown on religious symbols.

(more...)

Bread and Wine

Bread and wine represent the body and blood of Christ in the sacrament of Communion (the Eucharist).

An alternative symbol is that of wheat stalks and a bunch of grapes, elements linked to the Earth’s bounty and God's provision for humanity, and the main ingredients of bread and wine.

Bread and wine were primary staples in the ancient world, particularly in the Mediterranean regions, so it's not surprising that they were used in pre-Christian rituals as offerings to deities, or for fertility rites. In Greco-Roman religions, such as those associated with Dionysus (Greek) or Bacchus (Roman), wine had a central role in sacramental rites, often symbolizing divine intoxication or communion with the gods. Bread was also commonly part of sacred feasts.

(more...)

Crossed Keys

In Christianity, the crossed keys symbolize the two keys to the Kingdom of Heaven and represent the authority Christ gave to St. Peter.

In pre-Christian religions, most ancient references to keys come from Roman mythology, particularly from Janus, the god of doors and gates. Janus was believed to hold the keys to Heaven's door.

This doesn't necessarily mean that St. Peter's keys were copied from pagan ideas. Keys are everyday objects, so it's not surprising that they appeared in various ancient cultures. As in modern times, keys symbolized power and authority.

(more...)

Shell

The scallop shell, with its three graceful folds converging at a single point, mirrors the unity of the Holy Trinity. Each ridge speaks of a distinct presence, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, yet together they flow as one, a natural emblem of divine harmony. In baptism, the water it holds becomes a living symbol of this threefold grace, washing over the believer in renewal and rebirth.

Beyond its role in baptism, the scallop shell also represents pilgrimage, most notably journeys to the shrine of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in Spain, where pilgrims would often carry or wear the shell as a token of their devotion.

In pre-Christian contexts, the scallop shell was a potent symbol of fertility and love, especially in ancient Mediterranean cultures such as Greece and Rome, where it was associated with the goddess Venus (Aphrodite). Beyond fertility, it marked sacred journeys; shells were sometimes left at holy sites or worn by travellers as protective charms. A lesser-known fact is that some Roman coins depict Venus emerging from a scallop shell, underlining the shell’s enduring link to both divine beauty and sacred movement.

(more...)

Newman wrote in his 1845 Essay on the Development of the Christian Doctrine:

"The use of temples, and these dedicated to particular saints, and ornamented on occasions with branches of trees; incense, lamps and candles; votive offerings on recovery from illness; holy water; asylums; holy days and seasons, use of calendars, processions, blessings on the fields, sacerdotal vestments, the tonsure, the ring in marriage, turning to the east, images at a later date, perhaps the ecclesiastical chant, and the Kyrie Eleison, are all of pagan origin, and sanctified by their adoption into the Church."