Norman Cross

Normandy is a relatively small area in the north of France. Except for two islands under British sovereignty, the area covers about 5% of France - about the same size as Hawaii, but not as hot.

The region's name comes from 'North men'; the Vikings who conquered the area in the 9th century. Belgian Celts and Romans had previously settled there so one might expect the Norman Cross to be a mixture of the Celtic Cross and the Latin Cross. However, no such symbol is particular to the region since their influence largely ended long before the development of heraldry.

But there are several things which do bear the name Norman Cross:

The first is the symbol used by the secret society Sigma Chi, which is often referred to as a Norman Cross, but this is a misnomer. They have used a White Cross since the society's founding in 1855.

Sigma Chi is one of the USA's largest and oldest all-male college fraternities and it has never had any particular connection with Normandy; rather their emblem reflects the commitment of Roman Emperor Constantine, who saw a cross in the sky as he prepared to battle near Rome (a long way from Normandy). Constantine's emblem was chosen by the fraternity founders in the form of a White Cross.

The story goes that during the Civil War, Confederate Army soldier Harry St. John Dixon, founder of the Sigma Chi, fashioned a badge from a silver half-dollar using his pocket knife and a file. Starting with the circular disc, he made a Consecration Cross, flattened the arm ends, and mounted it on a long shield, resulting in the fraternity's emblem.

Why do they call it a Norman Cross? Sorry, but that's one of their little secrets.

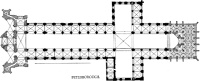

Another Norman Cross is the description used for a particular design of church.

The Normans typically built churches with a tower at the intersection and transept, as shown in this plan of Peterborough Cathedral. (Click image to enlarge) The style went out of fashion in the early 13th century.

A further Norman Cross is a tiny hamlet near Peterborough (map)

The Romans had earlier built the Great North Road (Ermine Street) and from that a branch north-eastwards to Peterborough. For the Normans, this would have been an important junction and most suitable for them to erect a Wayside Cross, although no trace of such has survived.

What is there, however, is a memorial to 1,770 French and Dutch prisoners of war who perished at the nearby Norman Cross Prison Depot during the Napoleonic Wars.

It is coincidental that the field was named Norman Cross and rather ironic too, considering the Normans invaded England 730 years earlier. There were Norman strongholds in old Roman towns to the north and south of Peterborough (in Lincoln and London) and they built the cathedral in Peterborough which still stands today.

The site covered about 40 acres and housed up to 7,000 prisoners. (To put this overcrowding in context, the grim 1970s Maze prison near Belfast to hold paramilitary prisoners covered 360 acres and never held more than 2,000 inmates.

Each of the Depot's barracks had two floors and measured 6.7 x 30.5 metres, giving a total floor space of 408 square metres. With 500 men in each building, there was less than one square metre per person. Sleeping on tiers of hammocks in such crowded conditions, primitive sanitation and hygiene; it was not surprising that disease was rife.

More than 1,000 died from a typhoid epidemic in the years 1800 and 1801. Typhoid causes a fever as high as 40°C (104°F), profuse sweating, delirium, gastroenteritis and diarrhoea, and the illness spreads through food or water contaminated by infected faeces. In other words, the Depot became a slow death camp.

The memorial at Norman Cross, shown above and fine though it might be, stands to show the shame on the British government for allowing so many conscripts to die. But such is war. One wonders what tribute governments today are planning for the current internment camps around the world.

One suspects that nobody has even thought about it.

There is a scarcity of natural stone in the Peterborough area and plundering by farmers and house builders was a common fate for such crosses.

A few died, mainly through hunger strikes.

Yet even today, in Peterborough, there are overcrowded camps occupied by foreigners. Italians came over in the 1950s, Asians in the 60s and 70s, and more recently, East European seasonal farm labourers. Not qualifying for state benefits and paid meagre wages if they manage to find work, many are crowded into poor quality housing or sleep rough in the fields. Peterborough seems destined to be bad news for foreigners.